The Topography of the Body:

The Artworks of Johanna Qiao Tong

by DAVID EGGLETON

Article from Art New Zealand Autumn Issue No. 161 / 2017

Self-portraitists know that the longer you look at yourself, the more estranged you become. Self-scrutiny isolates the intensity of looking, and whereas taking a selfie with a smartphone flattens and homogenises that experience, the self-scrutiny embodied in a painting deepens and enriches the engagement with the thing in the mirror.

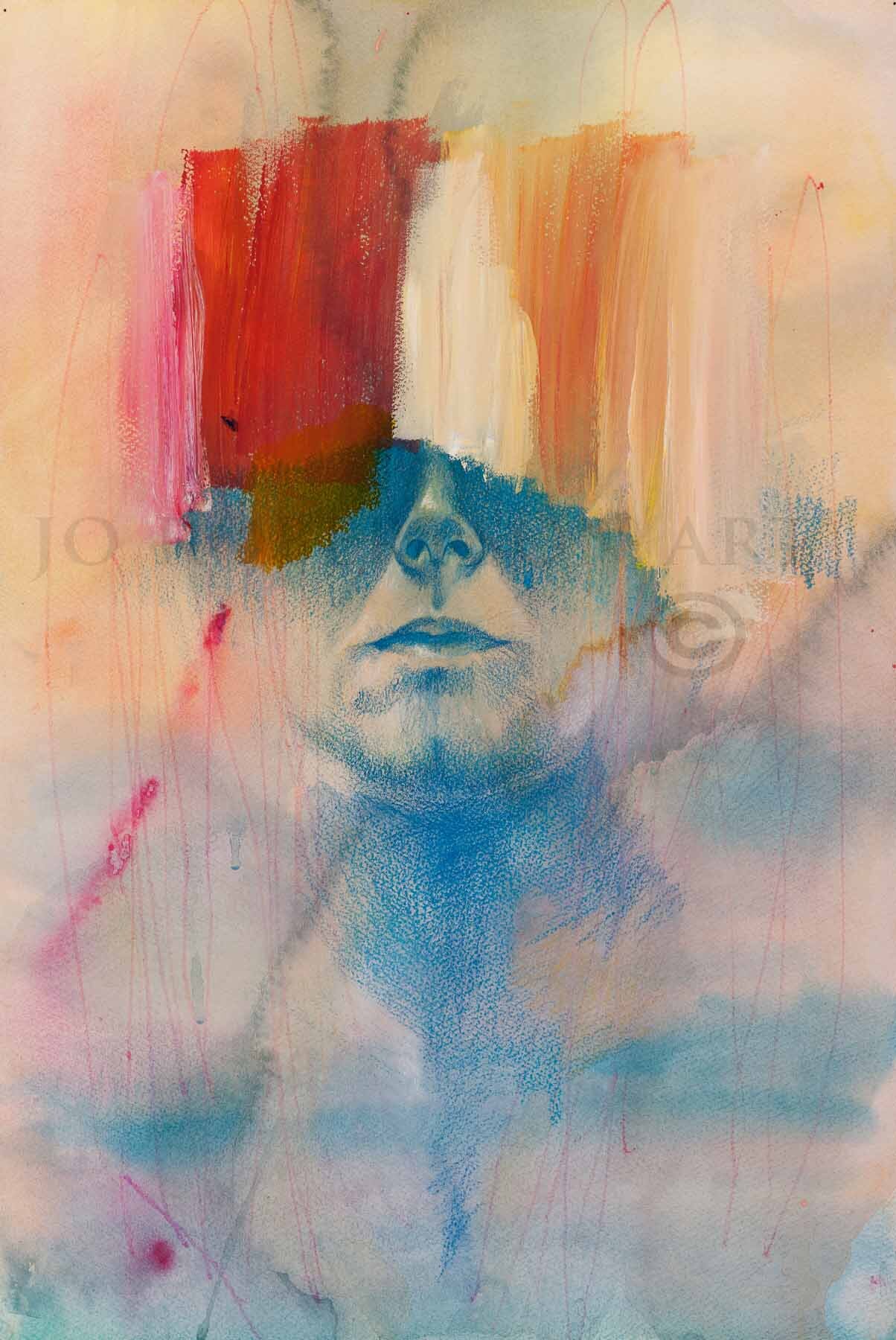

Johanna Qiao Tong, an autodidactic artist who characteristically uses herself — her body — as her subject, draws and paints self-depictions that are sculptural, angular, blocky, monumental, and often fragmentary. Her graphomania teases states of being out of a flux of swirls, squiggles, twists and streaks of pencil, pastel, charcoal, paint. Francis Bacon compared paint to a bodily secretion — like a snail leaving its trail of slime — and Qiao Tong’s sequences of life-studies — her test-piece formulations of eye, lip, hand, torso — imply the same.

Johanna Qiao Tong was born in Gore in 1983 and grew up mostly on farms in the South. She currently lives and has her studio at Middlemarch on the Strath Taieri plateau, an hour inland from Dunedin. At the foot of the Rock and Pillar range, this region is subject to hot winds gusting in summer and severe hoar frosts in the stillness of winter. Over the past fifteen years, Qiao Tong has moved studios back and forth between Dunedin and Middlemarch. She began to paint and draw as a child and says: "When I left school, I knew what I wanted to paint. I didn't want to spend three years at Art School, finding out something I already knew."

In Dunedin, working in old warehouse studios, her early work became associated with the grunge aesthetic of Alastair Galbraith, Michael Morley, Ben Webb and James Robinson. It showed, too, some evidence of the influence of the early Jeffrey Harris. Since 2003 she has exhibited steadily at various galleries in Dunedin, Invercargill, Gore, Oamaru, Timaru, Ashburton, Christchurch and Wellington. At all times, her work as a serial self-portraitist has involved a studied manipulation of the standard artistic tropes for self-depiction. This obsessive stylised interest in the topography of the female body — torqued, netherworldly, solitary, allegorical — bears comparison with an array of similar female artists: from Artemisia Gentileschi to Laura Knight, Jenny Saville and Helen Chadwick, as well as the New Zealanders Evelyn Page, Lois White, Rita Angus, Louise Henderson, along with the theatrical tableaux of the photographer Christine Webster. All of these artists made unsparing life-studies using themselves as the model.

But Qiao Tong’s exuberant body consciousness also, it seems to me, channels the dour hardiness of what one might call rural Otago Gothic, that is: the skyscapes of the Strath Taieri, the husk and bark of winter trees, stark as limbs; the mouldings of hills, the shapes and textures of rocks, fence wire, scrap metal, horses. There's an intimation of seeds, grasses, dirt, mud, rain: a contained poetry of light and shadow and dust. Her expressive mark making, for a time, favoured creased and crumpled and crinkly surfaces, and in particular wide swathes of tough brown dress-maker's paper, because rolls of it were cheap to buy.

This plentiful supply enabled her to maintain a spiky, barbed approach to image production. Not only did she stage over and over brutal collisions, applying flurries of paint fluently and at great speed in order to hatch at the centre the most finely-worked photorealistic detail, but she was liberated into a slapdash dynamic in producing work which could be censured, cancelled, erased, obliterated without agonising about the cost. Such works had a very high destruction rate: she ended up destroying much of whole sequences by burning them in paddock bonfires.

If this kind of practice extols the primitive, the crude, the raw, the unfinished, it can also capture, or entangle in paint, what she is striving for: a sense of the feral, of wildness, danger, violence — along with notions of duality, irony, ambivalence. We catch sight of streamlined figures, fully formed in places, notional in others, being catapulted from murk into the open — and reminiscent of birds of prey in flight. Some of these figures take on an alien or perhaps heraldic quality. There are intimations as well, in her fleshy bodily forms, of creatures curved and amniotic. These, uncovered, are floating on wake upon wake, fold upon fold, of vaporous slathering. This slather of paintwork brings to mind furled reefs of cloud, or inland fog and mist. And there, on this sun-shot baroque cloudwrack, a phantasmal head in tranquil meditation will also sometimes be propped-up. Gravity is a constraint yet the flesh is buoyant.

A weightless airborne body suggests a spiritual state, while a figure half-seen and diaphanous might be an apparition. And, as if in reaction or response to too much evanescence, Qiao Tong will zero in on a single staring eye or a raised hand and make that the firmly-contoured centre, amid all the amorphousness, the dissolves and the fades, the hauntings, doublings and shadowplay, the superimposed layers of blurry brushstrokes, the colours that blend into one another.

To start with, Johanna makes photographic studies, taking dozens of photographs in order to capture or pin down a certain precise depiction of her body in an arrested movement. She takes these photographs of herself with a camera set on a timer, and then works from the chosen images set up on a computer screen alongside her easel. Sometimes paintings and drawings are worked up from numerous images overlapping. For any given work, layers might be built up in dabs and jabs — fragments of information and feeling — constantly being adjusted, or amplified, exaggerated. For example, a drawing of fingers, might depict them as clustered as a big crowd, pointing, and jostling one another. Fluttering biomorphic shapes, they evoke shimmering moths or hovering butterflies, the beating of bird wings, the waving of grasses and leaves. At the same time, her repeated use of set movements of hands and limbs in particular bring to mind ritualistic and shamanistic dances. Johanna is a practitioner of various forms of Chinese meditation exercises including Qigong, and also a student of Indian mudras — or dance movements. For her, fingers are not just visceral objects but also emblematic of purification rituals: energy might drip off the ends of fingertips.

The sign-making fingers, the luminous single eye, the prominent whorled ear are perhaps religious emblems: the body as a holy temple. But if her depictions of tremulous fingers bring to mind the spectral conjurings of spiritual enchanters — the delicacy and precision of their execution complicates interpretation.

The fingers, filmy organic growths, wave like coral polyps gesturing from velvety deeps. Or are they finger puppets: phantasmagoric, tumultuous, tempestuous, ecstatic? Are these the constantly exercised fingers of a musician plucking the air, or the fingers of someone with a nervous condition? There's an element of self-mockery, as well as of the mock-heroic, about Qiao Tong's studies of the body: a sense that the body, any human body, has its own imperatives, denying the mind agency over its idiosyncrasies. This element of mockery is most noticeable in her series of self-portrait masquerades, where she turns her two hands into a harlequin mask, the quivering sense of touch that fingers embody becoming a clamped-on instant screen across the face, which is now concealed and disguised, cabaret-style.

So if sometimes her arcing bodies are foetal, curled, in a state of suspended animation, or in some liminal, oneiric state, implying almost an emanation, a soul; at other times the body might be a daemon or dancing devil, spiraling cloud-cauled and grappling with the air, or thrashing about as if bailed up in a net or trap.

Asserting and exploring female identity now, Qiao Tong's argument is with modes of depiction in a twenty-first century era of digital recombinations and extreme body consciousness: diverse, hard-sell, consumer-slick depictions of sexuality. Probing traditional mythologies of female deities, with gestures towards the embryonic, the womb-like, Johanna comes up with not so much Christian images of the Madonna in modes of forbearance but pagan idols: Dionysian maenads and bacchantes in their draperies, the sinuous curves of Hindu temple goddesses, or else slumbering Jungian archetypes. All these variations on the eternal feminine are presented with a kind of academic virtuosity that seeks to undermine — or correct — its own neat forensic skill with a kind of knowing messiness.

If oil paint once was a kind of sludge that might nurture ideals of beauty and delicacy, Qiao Tong challenges that with her figures' iconoclastic swinging arm gestures and vigorous push-back movements. If the dominant philosophical conundrum in art today is finding a way out of the ruins of painting, now that painting has been declared a played-out medium, Qiao Tong responds by scavenging through the debris of painting's grand narrative and reworking its left-overs. Out of this entropic situation and out of the abyss, from a formless chaos of pigment, she seizes a fragment, a body part, and portrays it with fidelity to a poetic mood, to a sense of the body as a sentient object in space, with eye, ear, tooth, shoulder-blade, finger-tip, alert, energised and embodying the life-force that also through the green fuse drives the flower.

BIO: David Eggleton is a Dunedin-based writer, poet and editor.